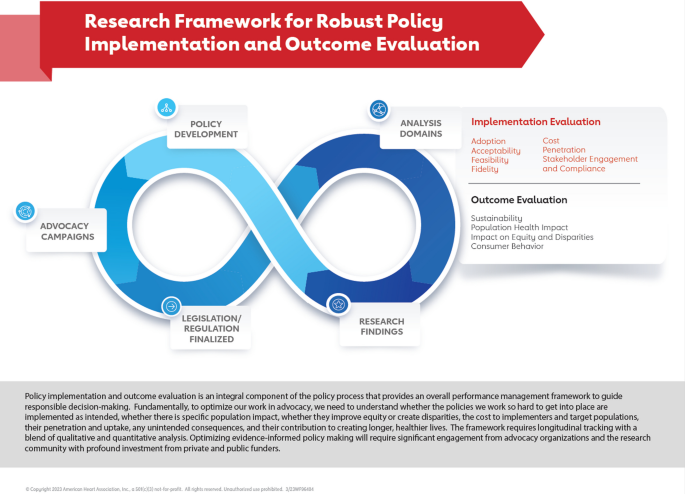

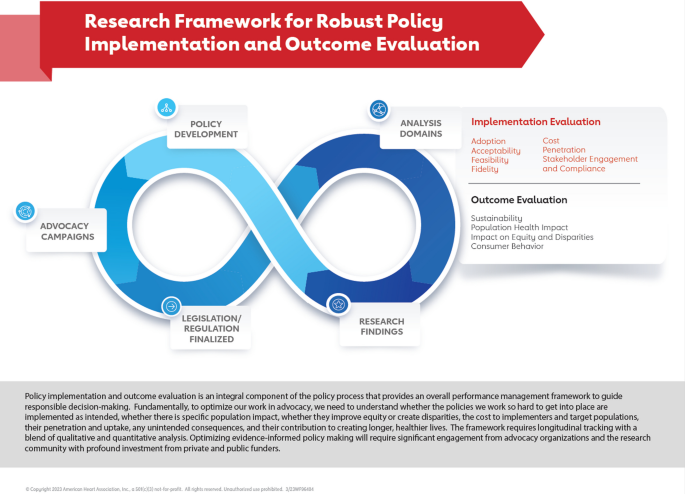

Advocacy organizations can play a crucial role in evaluating whether legislation or regulation has had its intended effect by supporting robust public policy implementation and outcome evaluation. The American Heart Association, working with expert advisors, has developed a framework for effective evaluation that can be used by advocacy organizations, in partnership with researchers, public health agencies, funders, and policy makers to assess the health and equity impact of legislation and regulation over time. Advocacy organizations can use parts of this framework to evaluate the impact of policies relevant to their own advocacy and public policy efforts and inform policy development and guide their organizational resource allocation. Ultimately, working in partnership, advocacy organizations can help bring capacity, commitment and funding to this important implementation and outcome evaluation work that informs impactful public policy for equitable population health and well-being.

Policy implementation and outcome evaluation, which assesses whether a particular public policy has had its intended impact when implemented, is an integral component of the policy process. It provides an overall assessment of the policy effects and can guide responsible decision making for ongoing policy development. Effective evaluation of how policies are implemented, scaled and funded can also inform decision making and prioritization by policy makers, funders, advocacy organizations and public health agencies [1]. Yet, it is significantly underutilized [2,3,4].

Many advocacy organizations, including the American Heart Association, are interested in an evaluation framework that helps assess the impact of the public policies they work to pass and implement. A framework that examines whether their resources and investments are optimally focussed on the most effective policies that can impact population health and whether there is equity impact would help guide organizational decision making. Evaluating the impact and outcome of public policy implementation allows advocacy organizations to engage with the research community to bring additional capacity for the kind of evaluation that can lead to evidence-based, equity-focussed policy making.

Advocacy organizations support social, public health or other causes that require changes in government, public policy or systems, often related to their mission. Advocacy organizations vary significantly in size, causes, structure/function and funding. The American Heart Association has a mission of being a relentless force for a world of longer, healthier lives and has done advocacy work for more than 40 years across issues related to prevention (tobacco, nutrition security, physical activity), acute systems of care, access to care, heart and brain research, digital health, public health infrastructure and appropriations. The organization has previously described how it is structured and functions in doing its advocacy work [5, 6].

Fundamentally, for advocacy organizations to optimize their work in public policy, they need to understand whether the policies they work so hard to get into place are implemented as intended. This includes whether the policies are associated with specific population impacts, whether they increase equity or disparities, what they cost to implementers and priority populations, the degree and scale of their penetration and uptake, whether they are associated with unintended consequences, and whether they contribute to creating longer, healthier lives. Effective evaluation assesses policy adoption, acceptability, penetration, feasibility, fidelity, implementation cost, cost-effectiveness, unintended consequences and sustainability [7, 8].

Table 1 provides definitions for each of these aspects of evaluation with equity considerations. A need exists to include quantitative metrics from relevant data monitoring systems to assess objective change or progress in health and equity over time [9]. Quantitative analysis has historically been under-utilized in policy implementation and outcome evaluation and is necessary to objectively assess population impact. [9] Relevant surveillance systems must be matched with the objective measures that will be tracked over time and the lag between data collection and public reporting of the surveillance data must be taken into account. Table 2 provides an example of a cascade approach to assessing health and equity impact longitudinally with quantitative measures. Equity domains may include income, educational attainment, race/ethnicity, geography, rurality, sexual orientation, gender identity, physical and mental disability, and other considerations specific to the issue area. While these metrics will primarily demonstrate association rather than causality with the policy change, the analysis will be important for assessing any impact on population health over time.

As we move forward into implementing parts of the framework, we will convene additional expert advisory groups to inform our evaluation and we will purposefully include people with lived experience.

Implementation and outcome evaluation is essential to optimize public policy efforts that aim to address inequities. Long-standing health disparities stemming from the historical, inequitable distribution of wealth, power and privilege and exist across almost every health indicator and outcome [13]. There is a need for equitable policy, systems and environment changes that are rooted in an understanding of the historical arc of structural racism and the influence of structural inequities on the proliferation of health-compromising conditions and the American Heart Association has issued a call to action identifying structural racism as a fundamental driver of health disparities [14]. Advocacy organizations can help catalyse public policy making at all levels of government to cultivate environments that support population health and well-being [13]. Policies are frequently passed with exaggerated claims of reducing inequities. Without implementation and outcome evaluation, there is little or no accountability measure to determine if those claims are met. Although there may be more attention and discussion of heath equity recently, research shows that this has not necessarily been translated into increased equity as policies are implemented. The overall health equity in mortality, for example, has slowed in recent decades, not accelerated [15].

The importance of evaluation and accountability is highlighted in What is Health Equity brief developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation [16]. It outlined three essential elements to achieve health equity as follows:

Engagement of under-invested communities is needed from the beginning of policy advocacy work. At each stage of the policy implementation and outcome evaluation process there are important questions to examine the potential impact on locations and community groups most burdened by inequities.

The review by Brownson et al. provides the following 10 recommendations as a pathway for advancing health equity through implementation science: ‘(1) link social determinants with health outcomes, (2) build equity into all policies, (3) use equity-relevant metrics, (4) study what is already happening, (5) integrate equity into implementation models, (6) design and tailor implementation strategies, (7) connect to systems and sectors outside of health, (8) engage organizations in internal and external equity efforts, (9) build capacity for equity in implementation science, and (10) focus on equity in dissemination efforts’[17].

Advocacy organizations cannot do policy implementation and outcome evaluation unilaterally. They must do it in partnership with academia, public health departments, funders, coalition partners, those with lived experience and other key collaborators. Only through partnering and collaboration can organizations bring the necessary capacity to this work. There are several key steps that advocacy organizations can take to facilitate greater commitment and collaboration around public policy evaluation. Depending on their capacity, mission-focused priorities, partner engagement, and community context, advocacy organizations may focus on some or all of these key steps:

If advocacy organizations can commit to facilitating, initiating and advocating for policy implementation and outcome evaluation in public policy, there is the opportunity to develop more impactful policy, understand the health and equity impact of legislation and regulation across the population, and guide organizational decision making and resource commitment. Engagement with funders, key collaborators, the research community, policy makers, government agencies, those with lived experience and public health is essential to bring the necessary capacity, resources and commitment to this work. Partnering with public health agencies is especially important to optimize the impact of funding to states and communities, improve population health monitoring and inform public health frameworks. The American Heart Association will use the framework to guide efforts to better capture the reach and impact of the public policies that we have worked to pass. Capturing the reach and impact of enacted policies will help us understand how our advocacy efforts have contributed to our organizational impact goal and strategic priorities. We will also disseminate this framework to our key partners and collaborators and to the research community. Together, with significant collaboration and coordination to achieve robust public policy implementation and outcome evaluation, the American Heart Association and other advocacy organizations can play an important role in informing the most effective public policy strategies to support population health and well-being.

We would like to acknowledge the thoughtful, impactful contributions of time and expertise from an expert advisory group we convened to start this work: Jamie Chriqui, University of Illinois—Chicago; Carlos Rodriguez, Wake Forest University; Darwin Labarthe, Northwestern University; Donald Lloyd-Jones, Northwestern University; Mary Story, Duke University/Healthy Eating Research; Keith Churchwell, AHA Past President; Amy Yarock, Gretchen Swanson Center for Nutrition; Laura Leviton, Special Advisor; Whitney Garney, Texas A & M University; and Angie Cradock, Harvard University. We also want to acknowledge the many experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who provided their review and input, especially Michael Schooley, Christopher Jones, Heidi Blanck, Erika Fulmer, and Carrie Dooyema. A special thanks to Yu Wang for her thoughtful feedback.